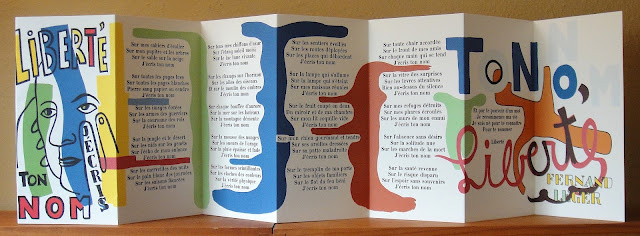

Liberty I Write Your Name ,

Paul Eluard and Fernand Léger, 1953

This accordion was published a year after Paul Éluard's death in 1952, and was commissioned by the French publisher, Pierre Seghers who invited Éluard's old friend and fellow communist to illustrate his famous resistance poem. Seghers wished to publish Liberté in honor of the memory of this esteemed French poet and former member of the French Resistance.(1)

Paul Éluard (1895-1952) was one of the founding members of the Surrealist movement and who emerged at the end of WWII as a national hero not only for his resistance activities, but more particularly for the psychological and moral uplift that his poem Liberté gave to the French nation in their time of need during the German occupation.(2)

Written in the summer of 1941 and first published a year later in an underground publication Poetry and Truth (1942) , the poem was also printed in leaflet form and dropped by the Royal Air Force over the occupied territories in France. The poem however, was never intended to become a symbol of resistance but started its life as a twenty-one quatrain titled Une unique pensé and was originally dedicated to Éluard's second wife Maria Benz (aka Nusch). Éluard takes up the story:(3)

I thought of revealing at the end the name of the woman I loved and for whom this poem was intended. But I quickly realized that the only word I had in mind was the word Liberté. Thus, the woman I loved embodied a desire greater than her. I confounded it with my most sublime aspiration, and this word Liberté was itself in my whole poem only to eternalize a very simple will, very daily, very apt, that of freeing oneself from the occupation. (4, 5)

One important element of this accordion, and a feature that often does not get mentioned, is that it utilized the pochoir printing method. In this example it was Albert Jon who created the stencils and hand applied the pigments, and this accounts for the vividness and texture of the blocks of color, and the work's overall vitality and presence.(6)

Examining this accordion within its larger cultural context, it's clear that this collaboration between writer and artist falls within the genre of books that came to known as Livre d'Artiste or Livre de Peintre . This genre of books by famous authors, accompanied with illustrations by equally well-known artists, was a practice that developed in France in the mid-1890s. This market for deluxe editions coincided with the period's growing art market and these books appealed to the new audience for the fine arts. While the majority of these books did not transcend their status as illustrated books of poetry and writing, they did establish the livre d'artiste as the forerunner of what we now call “artists' books'” in the post-WWII period. Johanna Drucker, an artists' book historian, in the following text examines what she sees as the key differences between a livre d'artiste and an artists' book when she writes that 'livre d'artistes':

“…stop just at the threshold of the conceptual space in which artists' books operate. First of all, it is rare to find an livre d'artiste which interrogates the conceptual or material form of the book as part of its intention, thematic interests, or production activities. This is perhaps one of the most important distinguishing criteria of the two forms, since artists' books are almost always self-conscious about the structure and meaning of the book as a form.”(7)

Furthermore, she notes that “…the standard distinction between image and text, generally on facing pages, is maintained in most livre d'artistes ,” while noting the often excessive production values and materials used in their creation. In conclusion, she pinpoints the differences between the two kinds of books stating that in livre d'artistes “the images and text often face each other like new acquaintances across the gutter, wondering how they came to be bound together for all eternity in the hushed , mute, interior of the ponderous tome.”(8)

The question that now begs to be asked is whether Liberté is a livre d'artiste or an artists' book. While there is no doubt that this accordion falls within the tradition of the livre d'artiste, I would assert that it's also balanced on the edge of being an artists' book. A number of features about this accordion leads me to this conclusion. Firstly, there are three elements to this work, Léger's portrait of Éluard, the poem itself, and the pochoir by Albert Jon. What, arguably, differentiates this publication from a livre d'artiste is that all these three elements have been fused together within the unique space of the accordion, and a key feature of this unity is how they've been brought together through a judicious use of the stencil technique.

While this accordion might not reach the threshold that Drucker claims for an artist's' book, I believe that it moves beyond the typical formal features of the traditional livre d'artiste and in binding together all its formal elements into an indivisible whole it moves closer to a definition of an artists' book. Aside from these formal considerations it's clear that this book also served a larger symbolic role for French audiences as a metaphorical flag for both human freedom and individual liberty.

To complicate matters regarding the definition of this publication, I want to turn to a small invitation card issued by the publishing house inviting people to the public reception for this book. The text reads:

Mr. Louis Carré and Mr. Pierre Seghers, publisher,

have the honor to invite you to the presentation

of the poem-object

Freedom

of

Paul Eluard

illustrated by

Fernand Léger

Friday, October 23, 1953 at 4 p.m.

What particularly interests me about this invitation is the description of this accordion as a poème-object, or in English 'object poem'. André Breton coined this phrase to describe his works that combined both text and poetry with three-dimensional objects. Breton defines a poème-object as, “…a composition that tends to combine the resources of poetry and the plastic arts, and to thereby speculate on their power of reciprocal exhilaration.”(8)

In its moving cry for liberty and resistance to the occupation Liberté combines both painting (pochoir) and poetry, two of the features of Breton's definition of the "poème-object", and when we shift focus to the “objet” of this poème-object we can only conclude that it is the accordion itself.

Stephen Perkins, 2024

note : footnotes at end of document

Footnotes :

1. The title of the poem, Liberté: J’écris Ton Nom, translated into English is, “Freedom: I Write Your Name.” The accordion had a second printing in 1953 and then other reprints in 2016 (French and European Publications Inc.) and 2022 (Pierre Seghers). Other versions with different artists’ illustrations have been published in 1998 and 2012. The present 1953 version was printed in an edition 238 copies.

Eluard’s birth name was Eugène Émile Paul Grindel, and Eluard was a name derived from his maternal grandmother.

2. This poem still has an honored place in rallying the national psyche of France. When the terrorist attacks took place in Paris on November 13, 2015, the Centre Pompidou hung an enlarged copy of the accordion’s front cover with Leger’s portrait of Eluard and the work’s title on the front of the building in response to the massacre.

3) Gramatzki, Susanne, Poetry in dialog: Paul Éluard’s Liberté as a fanfold, in: Christoph Benjamin Schulz (editor), Die Geschichte(n) Gefalteter Bücher: Leporellos, Livres-Accordion und Folded Panoramas in Literature und Bildender Kunst. [The Histories of Folded Books: Leporellos, Accordion Books and Folded Panoramas in Literature and Fine Art], Georg Olms Verlag: Hildesheim, Zurich, New York, 2019, pgs. 203-223.

4. https://www.trioletrarebooks.com/pages/books/2243/paul-eluard-ill-fernand-leger/

liberte-jecris-ton-nom, accessed 3.5.24

5. Below is the poem translated by Ben Platts-Mills: www.benplatts-mills.com/post/ on-freedom-paul-%C3%A9luard-s-poem

Freedom

On my school notebooks

On my desk and on the trees

On the sand on the snow

I write your name

On pages already read

On all the white pages

Stone blood paper or ash

I write your name

On golden icons

On the weapons of warriors

On the crowns of kings

I write your name

On the jungle and the desert

On the nests on the broom

On the echo of my infancy

I write your name

On the wonders of night

On the white bread of days

On the beloved seasons

I write your name

On all my blue rags

On the pond weeded sun

On the lake living moon

I write your name

On the fields on the horizon

On the wings of birds

And on the mill of shadows

I write your name

On each puff of dawn

On the sea on the boats

On the crazed mountain

I write your name

On the froth of clouds

On the sweat of the thunderstorm

On the thick insipid rain

I write your name

On the glimmering forms

On the clamour of colours

On the stubborn truth

I write your name

On the wakened trails

On the routes deployed

On the overflowing squares

I write your name

On the lamp that shines

On the lamp gone out

On my home regained

I write your name

On the halved fruit

Of my mirror and my room

On my bed empty shell

I write your name

On my greedy and tender dog

On his prickling ears

On his clumsy paws

I write your name

On the sill of my door

On familiar things

On the flood of blessed fire

I write your name

On any willing flesh

On the foreheads of my friends

On each hand held out

I write your name

On the window of surprise

On attentive lips

High above the silence

I write your name

On my ruined asylums

On my fallen flares

On the walls of my boredom

On the emptiness without desire

On naked solitude

On the marches of death

I write your name

On health returned

On vanished risk

On hope without memory

I write your name

And by the power of a word

I start my life again

I was born to know you

To name you

FREEDOM

6 ) Pochoir (“stencil” in English) was a printing technique used widely in France during the early part of the 20th century, indeed Léger had collaborated with Blaise Cendrars and he'd also created pochoir illustrations for his 1919 novel titled “La Fin of the mode filmed by the angel N.-D”. By the 1930s and '40s stencil was declining as the master practitioners were fading away along with the rise of photomechanical reproduction. For more about this stencil based method of applying powdered colors by hand follow this link to a Metropolitan Museum exhibition catalog titled “Pochoir by Painters” (1989):

https://libmma.contentdm. oclc.org/digital/collection/p15324coll10/id/190871/

7) Johanna Drucker, The Century of Artists' Books , Granary Books, New York City, 1995,

pg. 3-4

8) Ibid, p. 4

9) See: https://www.andrebreton.fr/en/work/56600100199560?, accessed 3.27/24.

From, André Breton's autographed manuscript dated February 27, 1942 and published in Le Surréalisme et la Peinture ('Surrealism and Painting') in 1965. Breton writes that the first object poem was presented in 1929.