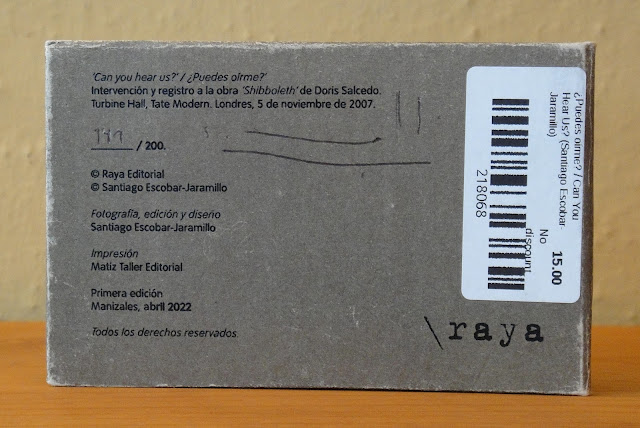

Based in Manizales, Escobar-Jaramillo is an architect at the National University of Columbia who received an MA in the Photography and Urban Cultures course at Goldsmiths College, University of London. He is also a photographer who has published a number of books and has been an active participant in international photography festivals.

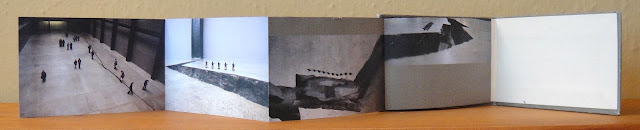

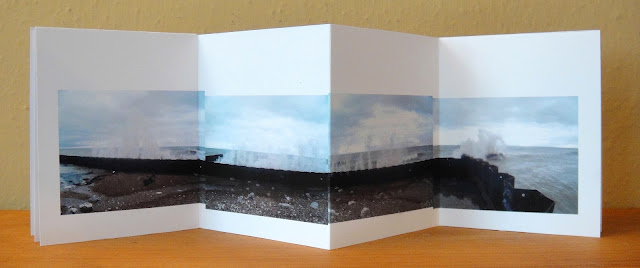

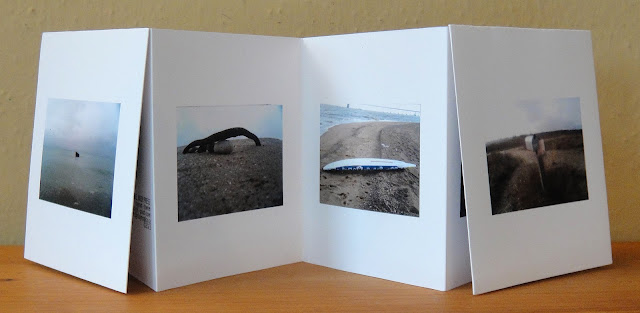

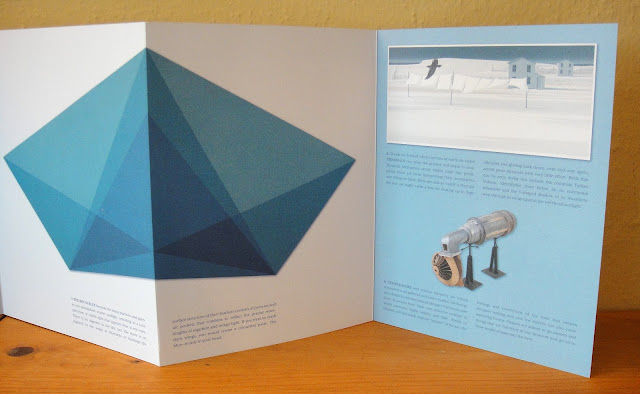

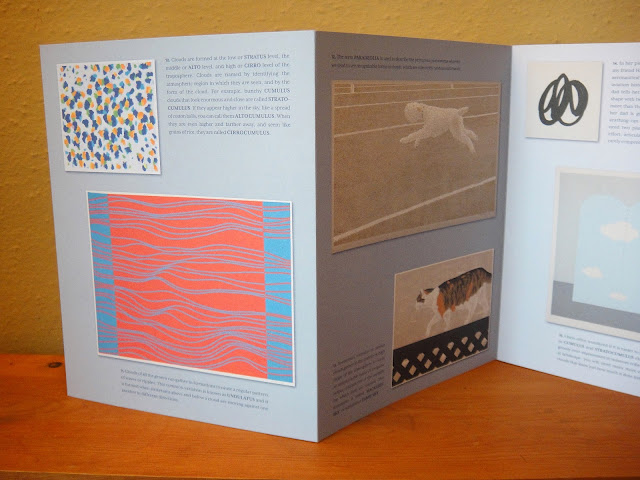

This work with its provocative sub-heading in both English and Spanish that reads: "'Can you hear us?' says the pavement at Brick Lane. 'Can you hear us?' cries the ground in Columbia," is illustrated by photographs of a work by another Columbian artist, Doris Salcedo that was installed in the Turbine Hall in the Tate Gallery in 2007. The work's title was Shibboleth which wikipedia explains as "any custom or tradition, usually a choice of phrasing or even a single word, that distinguishes one group of people from another," was part of Salcedo's Unilever Series and consisted of creating a physical crack in the Turbine Hall's floor that ran the length of the building, as shown in this accordion.

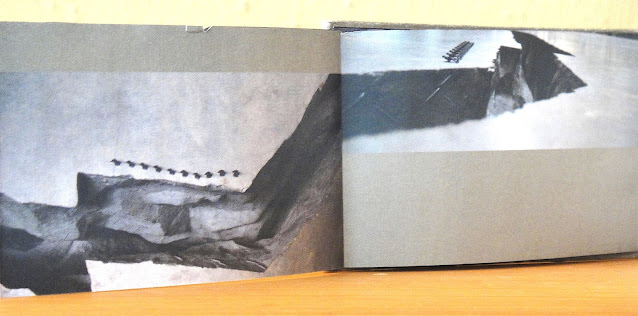

I'm assuming the military figures placed at the edge of the crack are part of an intervention by Escobar-Jaramillo and that they are in dialogue with both the political history of Columbia in which Salcedo had family members who were 'disappeared,' and the immigrant and working class history of London's Brick Lane. In a recent email to me Santiago states that the "...placement of the scaled-down soldiers in front of the intervention allowed it to no longer be seen as a crack but as a chasm: one that divides and separates us as a society."

I'll let the Tate Gallery's explanation of this work help us expand our understanding of the underlying themes of this installation, as well as Escobar-Jaramillo's interest in making this work around a fellow Columbian's literally ground-breaking piece.

"In particular, Salcedo is addressing a long legacy of racism and colonialism that underlies the modern world. A ‘shibboleth’ is a custom, phrase or use of language that acts as a test of belonging to a particular social group or class. By definition, it is used to exclude those deemed unsuitable to join this group.

‘The history of racism’, Salcedo writes, ‘runs parallel to the history of modernity, and is its untold dark side’. For hundreds of years, Western ideas of progress and prosperity have been underpinned by colonial exploitation and the withdrawal of basic rights from others. Our own time, Salcedo is keen to remind us, remains defined by the existence of a huge socially excluded underclass, in Western as well as post-colonial societies.

In breaking open the floor of the museum, Salcedo is exposing a fracture in modernity itself. His work encourages us to confront uncomfortable truths about our history and about ourselves with absolute candidness, and without self-deception."

5 double-sided pages, individually 1.75" x 4.25' and when fully opened 1ft 9.25".

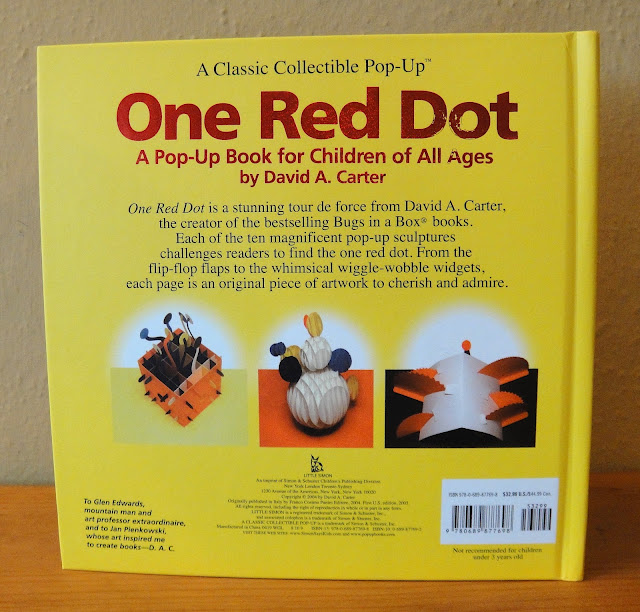

reverse

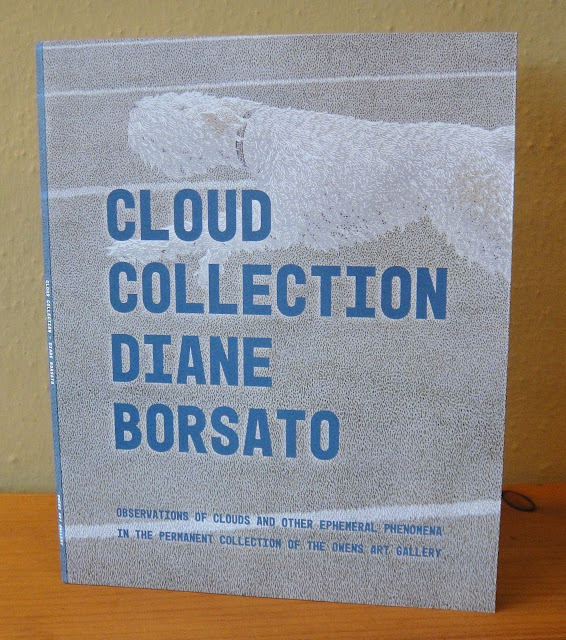

back of accordion